.png)

Snowpack conditions are off to a rough start this water year. Throughout the Northern Hemisphere, an abnormally warm winter has stalled snow accumulation in mountain regions.

Along the western coast of North America, heavy December precipitation driven by atmospheric rivers fell primarily as rain rather than snow. The immediate impacts were familiar: widespread flooding across the Pacific Northwest and less precipitation stored as mountain snowpack. This means a reduction in natural water storage available for the dry summer months. In the European Alps, vegetation above the treeline has increased by 77% since 1984, reflecting sustained warming at high elevations.

While there's still time left this winter to accumulate a nice snowpack, water managers are increasingly being asked to take on the challenge of predicting, analyzing, and interpreting snow conditions, especially in years that fall outside the normal range. In these scenarios, if and how snow information is incorporated into runoff forecasting can matter just as much as the observations themselves.

Across the snow science and water forecasting communities, there is ongoing discussion about which data are best suited to capture snow dynamics in a changing climate, as well as about how those data can and should be incorporated into forecast models to improve decision-making during volatile snow seasons. High-quality snow datasets are more accessible than ever—from long-standing monitoring networks to airborne LiDAR surveys—yet many of these observations are collected sparsely and are not consistently incorporated into operational hydrologic models. This gap between data availability and model integration helped motivate a set of experiments the HydroForecast engineering team undertook this winter.

>>> After experiments in predicting land surface conditions, provisional forecast outputs for Snow Water Equivalent (SWE) & soil moisture are coming soon to HydroForecast. Read the product announcement and sign up to be the first to get access when it’s available.

Rather than starting by asking what additional snow data to ingest, we asked a different modeling question: Can a hydrologic forecasting model learn snow dynamics well enough to predict Snow Water Equivalent (SWE) as an output alongside discharge, without relying on constant direct snow observations as inputs? And does doing so improve streamflow forecasts?

Before getting into the results of those experiments, it helps to first step back and examine how snow observations have traditionally been used in water supply and runoff forecasting.

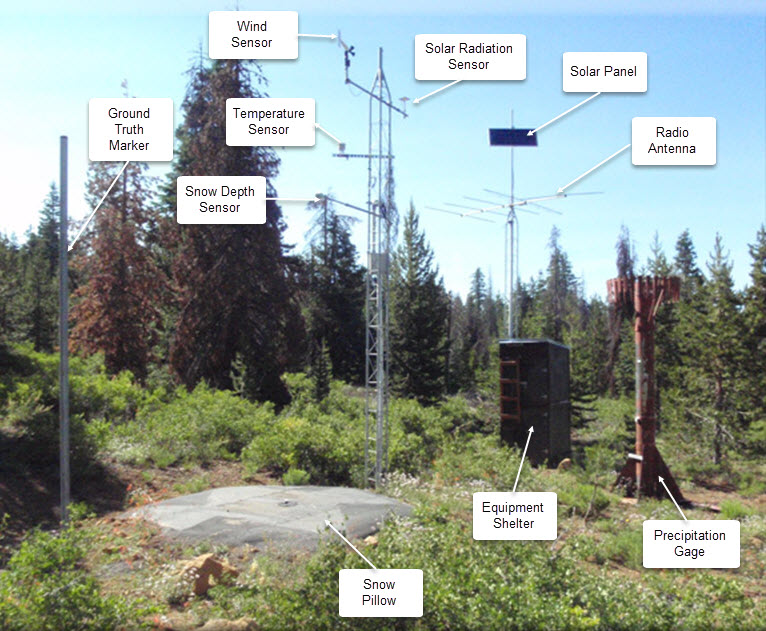

Snow observations have long played a central role in spring runoff forecasting. Networks such as SNOTEL in the United States and SLF in Switzerland have informed water supply forecasts for decades. These point measurements are maintained by field staff each year, and their value is well established as this data serves as the basis for many gridded snow models and products (e.g. SNODAS from SNOTEL sites).

Recent research indicates that strategically placed snow monitoring stations can outperform even high-resolution, basin-wide snow mapping when it comes to predicting spring runoff.

However, a warming climate introduces complications. As temperature regimes shift, historically representative monitoring locations may no longer sample the same snow processes they once did. A 2022 report found that the elevation of the rain-snow transition along the western slope of the Northern Sierra Nevada (California) has risen by roughly 1,200 feet (~370m) since the 1930s. Stations historically positioned to capture snowfall are increasingly exposed to mixed precipitation, reducing their ability to characterize basin-scale snow storage.

At the same time, advances in remote sensing have transformed snow observation capabilities. Programs such as Airborne Snow Observations (ASO) use LiDAR to map snow depth and SWE across entire watersheds at very high spatial resolution. These datasets provide unprecedented insight into where snow is stored and how it varies across complex terrain.

The struggle from a modeling standpoint is that typically this rich data is collected infrequently—often once or a few times per season due to cost and logistics. While there is much enthusiasm for these data, many in the user community find that integrating them into operational hydrologic forecasts remains an open challenge.

After our first experiments into how machine learning (ML) is suited to capture shifting snow dynamics, our team set out to learn if HydroForecast could predict SWE alongside discharge to improve streamflow forecasts.While our goal wasn't to produce a perfect SWE forecast, we used a joint prediction approach to encourage the model to better represent the physical processes governing runoff. By predicting SWE and soil moisture as internal targets, we ensure the model 'understands' the relationship between snowpack and streamflow without losing focus on the primary goal: accurate water supply forecasts.

Using our Long Short-term Memory (LSTM) deep neural network architecture, the HydroForecast engineering team trained a series of foundational model variants with the following configuration.

This configuration allowed the model to learn relationships between meteorology, snow storage, soil moisture, and runoff, while maintaining discharge as the dominant optimization objective.

Across most configurations, discharge performance either improved or remained stable. The strongest results came from models that jointly predicted streamflow, SWE, and soil moisture, where HydroForecast outperformed the baseline at roughly 70% of sites across ~480 foundational model sites. By predicting SWE and soil moisture as internal targets, the model demonstrates it can 'understand' the basin's state even between sparse physical observations.

These results indicate that the model is learning more realistic internal representations of hydrologic processes—improving both forecast skill and interpretability.

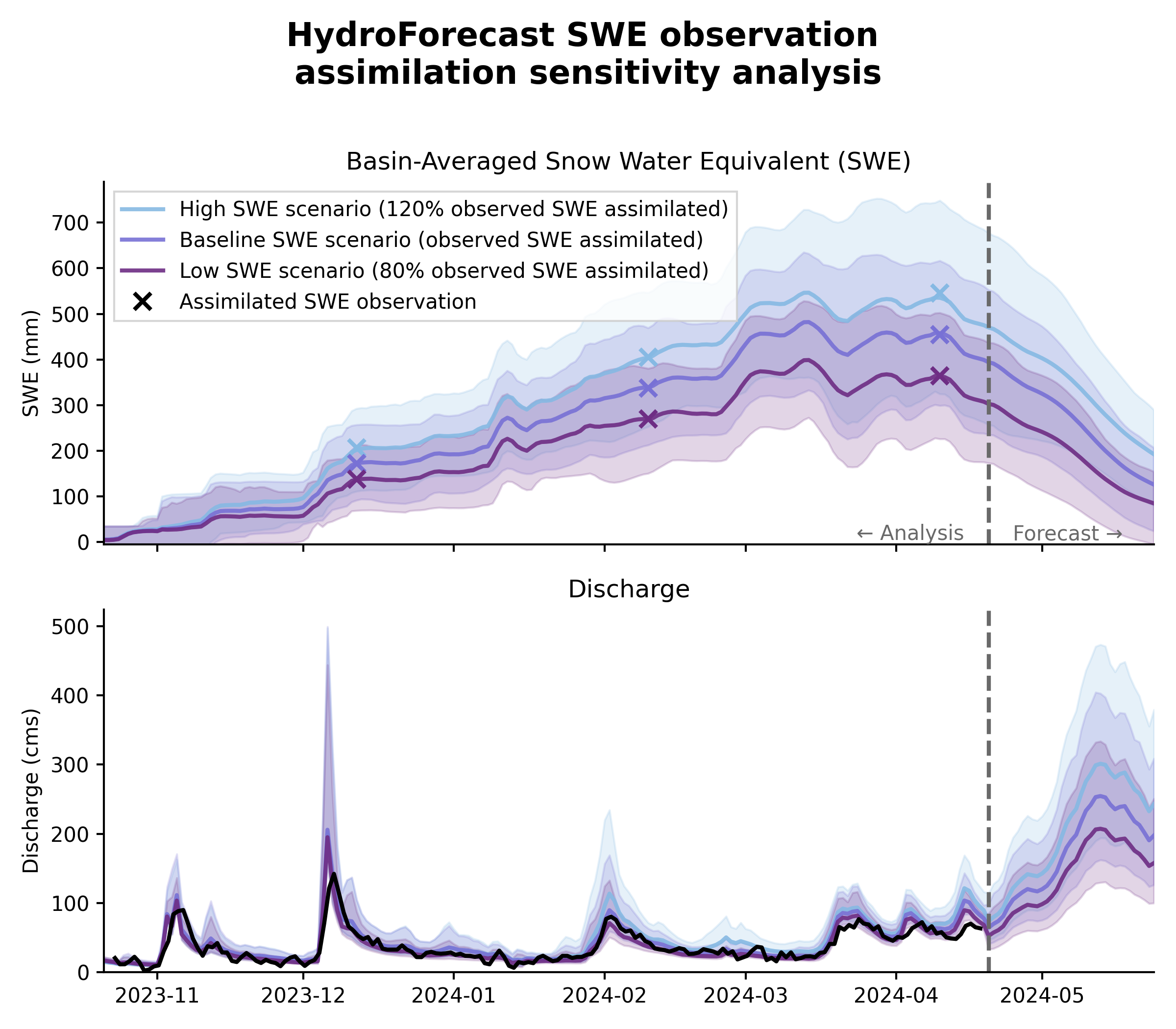

A key implication of this work is that HydroForecast does not require SWE as an input, but it can meaningfully incorporate SWE when observations are available—even if they are sparse.

To test this, we used the SWANN dataset from the University of Arizona. Rather than using the entire consistent time series as an input, we only provided the model with distinct data once every few months. This mirrors how sparsely available data from snow courses or ASO flights data would be incorporated into the model.

When these sparse SWE observations were introduced, we saw these intuitive patterns emerge across sites:

This behavior indicates that the model responds to SWE changes in a physically interpretable way, reinforcing that it has learned the functional role of snow storage in runoff generation.

Taken together, this work helps bridge the gap between modern snow observations and operational runoff forecasting, particularly in systems where snow data are sparse, or where snow dynamics are shifting in a changing climate.

We’re looking forward to incorporating these learnings into tangible improvements for HydroForecast customers, including new forecast outputs for SWE and soil moisture. If you’re interested in learning more about these forecast outputs as we roll them out, sign up to be the first to know.